Latest from Technology

Sponsored

Industry experts have been shouting from the rooftops for some time now about the benefits of district energy—those same rooftops which can house sustainable energy such as solar photovoltaic (PV)/thermal energy equipment. In fact, the global market for district heating and cooling systems is expected to expand to over $754 billion by 2032, this according to Armstrong Fluid Technology.

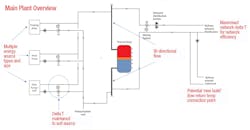

The idea behind district heating is simple: centralize water heating across a large enough system and what is wasted energy in one part becomes free energy in another. Improving efficiencies by incorporating multiple heat sources is the key—coupling the aforementioned solar technology with geothermal, combined heat and power (CHP), heat pumps, waste heat recovery and fluid flow technologies, just to name a few. Driving the adoption of district heating are a growing number of organizations committing to net-zero targets.

“District energy has been around for many years on college campuses and major cities—all that is really changing is that we are now moving this into the residential market,” says Tony Furst, MSEd, CPD, LEED AP, RSEC Manager—US Application Engineering, Armstrong Fluid Technology.

How this works, says Furst, is that the basic infrastructure would be built by the purveyor, no different than the electric companies and gas companies. “Once the infrastructure is in place in a neighborhood, the customer pays to install the piping from the street to their house, and the purveyor provides the heat transfer unit (HTU), no different than your gas or electric meter now.”

Equation Shift

But how do we change the calculus in old-school thinking and move on from, “this is the way we’ve always done it.” “We need to explain that district energy is no different than buying electricity or gas from your local utility provider, and most people don’t understand that businesses have waste heat or excess cooling capacity that can be repurposed to reduce overall energy consumption,” says Furst.

Most systems fail not due to faulty equipment but due to poor design. During system design, engineers need to be cognizant of transport energy loss along with what types of loads will be connected. “They also need to understand the use of thermal storage as a means to capture and store energy until such time that it is needed,” says Furst.

Furthermore, one of the biggest benefits for district energy is reliability, says Furst, “with no real worries about breakdowns as you won’t have a conventional furnace and air conditioner, you’ll have an air handler and coil similar to what you would have with an air source heat pump along with a heat interface unit (small heat exchanger). Depending on the district provider you may only have district heating or you may have a four-pipe system that provides both heating and cooling.”

When discussing heating systems, an advantage to low return temperatures is that one can use multiple heat sources to generate heat. “If we are using boilers, we can utilize condensing boilers which achieve their best efficiency—93% or better—when we can extract all of the latent energy contained in the flue gases. We can also easily use the rejected heat from data centers or other places that have a large cooling load in the winter. In the simplest terms, what we are doing is utilizing the heat that would normally be wasted to the atmosphere and redistributing to places that need it,” says Furst.

Inside the Numbers

Typically, reducing primary energy demand in heating and cooling by 50%, district energy installations can achieve operational efficiency of up 90%, according to the United Nations (UN) Environment Program.

The UN results are made possible in part by fluid flow technologies designed by HVACR manufacturers, and intelligent fluid management systems (iFMS) can now integrate superior pump and control technology into a single packaged solution that can save 30% or more over other parallel pumping configurations. Energy savings can exceed 70% compared to a constant speed system.

Modern variable speed controllers integrate with building BMS systems to provide best-efficiency modulation and staging of pumps, while serving as many as 16 zones.

When talking residential applications, diversity needs to be calculated in the efficiency equation. Diversity—in an HVAC sense—refers to the fact that building load is comprised of internal and external sources. Think about your house compared to your neighbors, says Furst. Do you all work the same hours, do you all go to bed at the same time? Are some folks at home while you are away? What about the sun, and is your house in the full sun all day? What direction does your house face, what about trees and shade? “Diversity is simply the variability that occurs in every HVAC system regardless of size because the imposed load in each building varies as the external forces change,” says Furst.

Proof is in the Field

After discussing options with both energy service provider Engie and the local Armstrong representative, city officials decided to proceed with Armstrong Design Envelope Intelligent Fluid Management System, Design Envelope ips 4002 controller and Design Envelope Vertical In-Line pumps, Key factors in the decision were the built-in capabilities for intelligent control and management. By integrating superior pump and control technology into a single pumping solution, the iFMS and ips 4002 together save 30% or more in energy over standard pump-sequencing systems.