Heat Pump Rescue - Struggle with a Crippling Error Code

I love working with copper pipes and fittings and circulators and valves. I love working with heat pumps and boilers and controls and making systems work well and rescuing those that don’t.

I love designing heating and cooling systems on screen and paper and then laying them out and installing them. There is something very satisfying about the tangible nature of installing copper pipe and sweating fittings and wiring motorized valves. I don’t mind designing and installing ductwork and making it beautiful—it too can be satisfying in its own way.

But I do not love working on impenetrable proprietary closed systems that resist all of our efforts to rescue them and get them to heat and cool correctly. Being defeated at every turn by an inflexible robot brain is not my idea of fun.

But many times we don’t get hired for a rescue to have fun; we get hired because we stick with it until we have figured out the issue(s) and made necessary corrections to achieve comfort and efficient operation.

This particular rescue was a real challenge as we had to figure out what was causing a crippling error code in a heat pump system that was driving the homeowner nuts.

System Worked Well (Until It Didn't)

The system was a modern multi-zone heat pump system with one outside unit connected to two branch boxes which served five inside units. The branch boxes had electronic expansion valves and talked to the wall controls and inside units; the two branch boxes then communicated to the outside unit. The system was sized using a Manual J heat loss and the manufacturer’s design software. All of the piping lengths and diameters were spelled out between outside unit and branch boxes and to all of the five inside heads.

The design software also spelled out the compatible wall controls, wire lengths, and type of wire.

According to the homeowner, the system worked very well the first summer. No issues with any of the five inside heads and very comfortable and efficient operation. Pretty vanilla installation that has been successfully installed both here in the US and globally.

Unfortunately, after the first summer, the homeowner started to get the same error code over and over that made no sense. What had been a successful cooling system was now a lemon! (according to the homeowner).

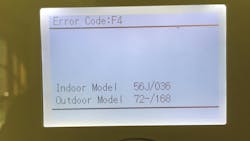

Chronic Error Code F4 that Made No Sense

The homeowner noted that during the cooling season, about once a month, the entire system would grind to a halt and flash F4 as an error code. In every other respect, the cooling was working quite well. All of the inside zones had great discharge air temperatures, and all zones were at setpoint, even on the hottest days.

So there was no rhyme or reason for this F4 error code: “Low discharge superheat across compressor which was determined by monitoring both suction and discharge temps across compressor and most likely caused by liquid flooding back to outside unit from indoor units”.

The homeowner had to turn off power to the five inside heads, the two branch boxes, and the outside unit, wait a few minutes, and then turn everything back on to clear the error code. This was quite frustrating for them and confounding for us.

Tech Support Just Reading the Script

We called tech support and were not surprised by the reply from the first level of support; they had us confirm again the length and diameter of the lines between outside unit and branch boxes and inside units. They had us pull off the wall controls to confirm the gauge and type of the wires between the inside units and the wall controls. They had us recover the refrigerant charge to confirm that we had the correctly calculated the refrigerant charge in the system.

All of that checked out and corroborated our original entries into the manufacturer’s design software.

If in Doubt, Replace Boards

They were stumped, so they recommended replacing the main PCB on outside unit. These boards are never fun to swap out and we had to take apart most of the outside unit to remove and replace the board. Then we had to wait patiently for the next appearance of the F4 fault code. Sure enough, a month later the F4 fault code appeared again.

Tech support then pivoted to blame the pressure sensors. We had to take apart the outside unit again (and recover the refrigerant charge) to remove and replace the pressure sensors. As before, we had to wait patiently for the next appearance of the F4 fault code. And sure enough, it came back a month later. As I mentioned earlier, this was not how I wanted to spend my rescue time!

Senior Level Tech Support – Finally!

All of our suffering with lower-level tech support finally paid off and we were admitted to the next level! We finally had someone that wasn’t just reading a script or a fault tree; they could actually think outside the box to look at our puzzling situation.

They suggested that maybe there was an issue when the pressure sensors were telling the robot brain what their pressure was. Because the system was working perfectly, and then it had an error code driven by pressure (and temperature) information, maybe the pressure reading was corrupted by a sudden drop in voltage on the control board?

It seemed like a stretch but at this point we were desperate. The homeowner was sure we didn’t know how to work on heat pumps and was lobbying to junk the entire system and have us replace it.

Start Data Logging

We set up our data logger on the power coming into the outside unit and set the sampling rate to one second. We had to visit the site quite a few times over the next month to collect the data and clear the data logger cache. No dips in power, but also no F4 error code.

Finally, the homeowner called to report the return of the F4 error code. We raced over and confirmed from the data logger that power had indeed dropped from 245 volts to 35 volts for half a second! Not long enough to make the microwave blink 12:00 or cause a computer to restart but long enough for the control board voltage to drop.

Our senior tech support guy surmised that if the drop in voltage happened when control board was trying to read refrigerant pressures, it would suddenly see catastrophically low pressures and shut down.

This was because each pressure sensor was fed 5 volts DC and then sent a return signal to the control board. If the pressure was suddenly fed 1 volt DC, the return signal to the control board would appear to be really low refrigerant pressure.

This was great news to finally find a culprit and be able to tell the homeowner that we knew why the fault was occurring.

Of course, all they wanted to know was: what were we going to do about it?

Manufacturer: Don’t Alter Anything – Homeowner: Rip it Out!

Now that we knew that intermittent voltage dips were causing the F4 error codes, we had to find a solution. The manufacturer said we should relocate the system to a location where there were no dips in voltage. Ha! That wasn’t very helpful here.

The homeowner didn’t want to continue suffering with a system that was so sensitive to incoming power quality. Meanwhile, the manufacturer said we would void the warranty if we altered their equipment.

Backfeed Sensors with 5 VDC?

At this point we were game for anything. We noted that the existing transformer on the heat pump control board was soldered in place. We didn’t want to try to solder anything onto the control board for fear of destroying it.

If we could somehow backfeed 5 volts DC onto this control board, we could make sure that board voltage never dropped and therefore there would never be another fake F4 error code.

We then powered that regulated power supply with a UPS (uninterrupted power supply) commonly used to protect computers.

We told the homeowner (but not the manufacturer) what we had done. We said that we would warranty the outside unit ourselves as we were confident that we had solved this (miserable) mystery.

The F4 error code never came back. The homeowner was finally happy, and we were glad to return to the world of hydronics and copper pipes and circulators!

About the Author

Brian Nelson

Brian Nelson is the co-owner of Nelson Mechanical Design, a “green” mechanical contractor serving the energy efficiency and home comfort needs of Martha's Vineyard, MA since 2004. The company designs, installs, and services just about anything to do with heating, cooling, domestic hot water, water treatment, geothermal, heat pumps, and radiant. NMD is committed to preserving the fabric of the Island it calls home. To learn more visit nmdgreen.com.