Latest from Best Practices

Sponsored

Top 3 hydronics questions asked in my training workshops

If you do something for a long time, eventually someone asks you, “What questions are you asked the most?” This is easy. The most-often asked question I get is, “How were you able to get Kathy to marry you?”

This is by far the hardest question to answer because, quite frankly, I have no idea. I think it involved a payout, but I’m not sure how or when. Now that we have five daughters and 16 grandchildren, she’s sort of stuck with me.

There are, however, other questions that are asked almost as frequently. I could discuss questions around plumbing, heating, cooling, snow melt, geothermal or other topics that I have taught. But for now, I’ll narrow the field to hydronic heating. Let’s take a look at the three most-asked questions I have received over the years.

Question 1: Do I have to insulate under a slab when installing radiant heat?

Let me tell you a story that helped solidify this question for me. Some years ago, a friend of mine built a slab-on-grade house over mostly sandy soil with no contact to the bedrock or stone ledges or any other particularly high-density material that would wick away the heat. The topic of insulating under the slab came up at this point.

He and I often argue about the value of under-slab insulation, and he takes the stance that even if some heat goes down into the soil, it will just add to the mass of the heat sink and will actually become a benefit on really cold days with more stored heat in the soil.

I would love to argue all day about this very topic, but for today, I’ll just finish the story.

My friend went on to build the house with no insulation under the slab except for four feet of perimeter insulation around the outside of the whole house. Oh, and he did insulate the walls and ceilings very well, but then he called it a day.

I joked with him, saying: “Well, that’s just great, except people don’t walk on the walls and ceilings, they walk on the floors.” Anyway, the way he built the house and insulated it, he installed a 75,000 BTU, modulating-condensing boiler, using radiant in-slab heat with ½" tubing placed 12" on center. He said he saved “a couple thousand dollars” on insulation costs.

Everything ran fine for several years, and he began to be quite annoying about how well the house was performing thermally — how comfortable it was and how inexpensive it was to run. I found his smirk disturbing.

From that day on, I stopped calling it insulation and started calling it insurance.

That all changed one summer when a 22-store strip mall was built about two blocks from his house. With an all-asphalt parking lot covering several acres, the water runoff was diverted to a newly built holding pond located a block from his house. All of a sudden, the ground water level rose underneath his house until it was less than a few feet from the bottom of his slab.

Then came winter. Much of his heat was now wicked into the rising groundwater. He increased his supply water temperature from 90°F to 140°F but the system was still unable to keep up, so he ended up installing another 40,000 BTU boiler to compensate. Two years later, he abandoned his radiant system, installed forced-air heating and carpeted over all his beautiful wood floors because his wife’s feet were cold.

My friend and I have never had another conversation about insulating under a slab, and somehow, we have still remained good friends. I always hide articles like this one from him just as a show of friendship.

My point is this: From that day on, I stopped calling it insulation and started calling it insurance. There is a very good reason insulating under a slab is a code requirement in many parts of the country.

Question 2: In a radiant heating in-floor system, does it matter how far down the tubing is placed in the concrete slab?

Absolutely, and I’ll explain why. Heat is a form of energy. Thus heat, like all forms of energy, does two things. It always flows from hotter to colder, and it always takes the path of least resistance (sort of like my brother-in-law). With those two rules in mind, take a look at the two illustrations below.

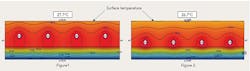

Figure 1 and Figure 2 are two images produced by a software package called HEAT2. The software models the thermal performance of an installation. It will predict where the heat will go and how much of the heat will be used up, and which direction the heat will go.

In this case, both models are using 95°F supply-water temperature with 6" on-center tubing. The yellow represents 2 inches of R-10 insulation, and the blue is the soil. Figure 1 has the tubing at a depth of 2 inches from the surface; Figure 2, 3-½ inches from the surface. For occupants in a home, the most important factor is the surface temperature.

The HEAT2 software predicts the average surface temperature of Figure 1 to be 27.7°C, while Figure 2 will have an average surface temperature of 26.7°C. The former is a 3.7% increase (1 ÷ 26.7) in surface temperature for the rest of the life of the installation just by placing the tubing in the middle of the concrete.

Heating systems that require lower return-water temperatures — geothermal ground-source heat pumps, solar, and condensing boilers — all benefit by being more efficient and consuming less energy.

To be totally forthright, both systems will provide the necessary heat to keep occupants comfortable, and the difference between these two is slight. I acknowledge that. It’s just a “best practice” installation. You decide.

That said, for commercial applications, I do understand the implication of ram-set nails that are driven into the concrete potentially punching a hole in the tubing if it’s just 2 inches below the surface. However, in typical commercial applications, the slab is 6 inches thick. Installing the tubing at a 3-inch depth will continue to provide the same performance without the risk of piercing the tubing (unless you are using 52-inch, ram-set nails).

Question 3: Which is better, baseboard heat or radiant heat?

This is tough because it is sort of like asking the question, “Which makes a better snack: broccoli or a candy bar? (Hint: always pick the one in a wrapper. The wrapper locks the flavor in and keeps the calories out.) Or, the more classic argument, “Great taste or less filling…which is better?”

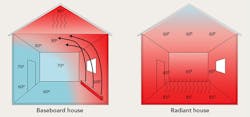

Baseboard heat and radiant heat are actually two very different heat sources. Baseboard heating produces convection heat, or heat that is transferred from one place to another by the movement of air. Radiant heating transfers heat by thermal radiation or electromagnetic radiation.

A baseboard heating system heats the air, which, in turn, heats people. Radiant heat transfers its heat to people directly. In a radiant system, a very slight amount of convected heat is produced right at the flooring. Baseboard heating produces a very slight amount of radiant heat right at the baseboard. The examples below help to illustrate these two processes.

Radiant heating is a high-mass, low supply-water temperature (often around 100oF), slow responding, more evenly distributed heat.

Baseboard is a low-mass, high supply-water temperature (often near 180oF), quick responding, more asymmetrical temperature system.

Baseboard heating is less expensive to install, but may not give the thermal comfort you desire. Radiant heat is more expensive to install than baseboard, but provides a more even thermal comfort.

At the end of about eight years, the savings from radiant heat — with its low supply-water temperature — overtakes the less expensive installation cost of baseboard heat. From then on, it will continue to provide more low-cost, comfortable heat.

The above differentiation might help you choose which application is best for a project. Once again, you decide.

So there you have it: my three, most-asked hydronic questions. Not that you would necessarily ask any of these questions. Maybe you’d want to talk about plumbing, or geothermal heating and cooling, or something else. If these questions aren’t what checks your boxes, drop me an email.

I would be grateful to hear your thoughts, ideas and stories. Until then, best regards and happy heating.

Steve Swanson is the national trainer at Uponor Academy. He actively welcomes reader comments and can be reached at [email protected].

Steve Swanson

Steve Swanson is the customer trainer at Uponor Academy. He actively welcomes reader comments and can be reached at [email protected].